Chapter 9 Transfer Learning for NLP II

Authors: Bailan He

Supervisor: M. Aßenmacher

Unsupervised representation learning has been highly successful in NLP. Typically, these methods first pre-train neural networks on large-scale unlabeled text corpora and then fine-tune the models on downstream tasks. Here we introduce the three remarkable models, BERT, GPT-2, and XLNet. Transformers is an excellent Github repository, where readers can find their implementations.

9.1 Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)

9.1.1 Autoencoding

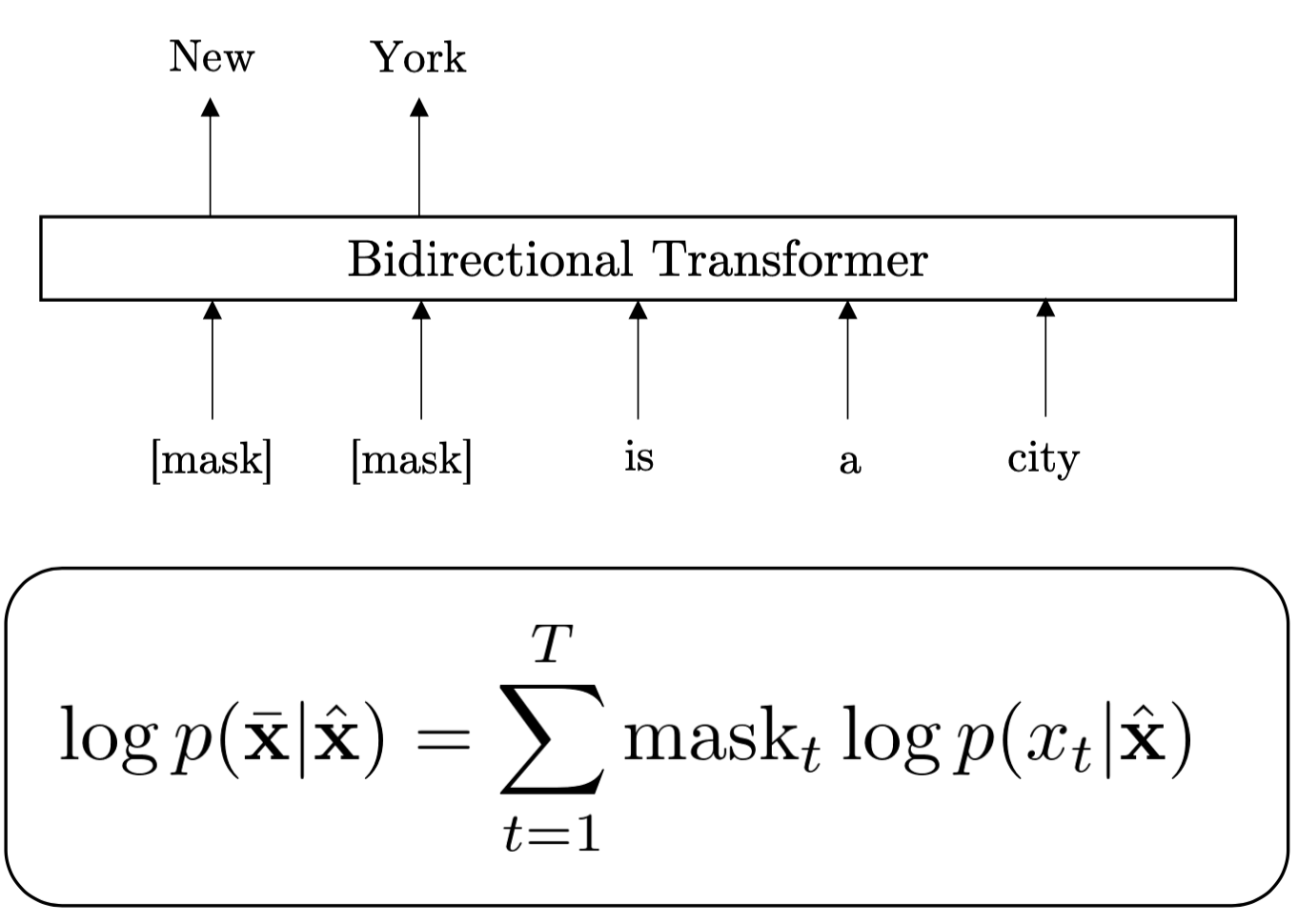

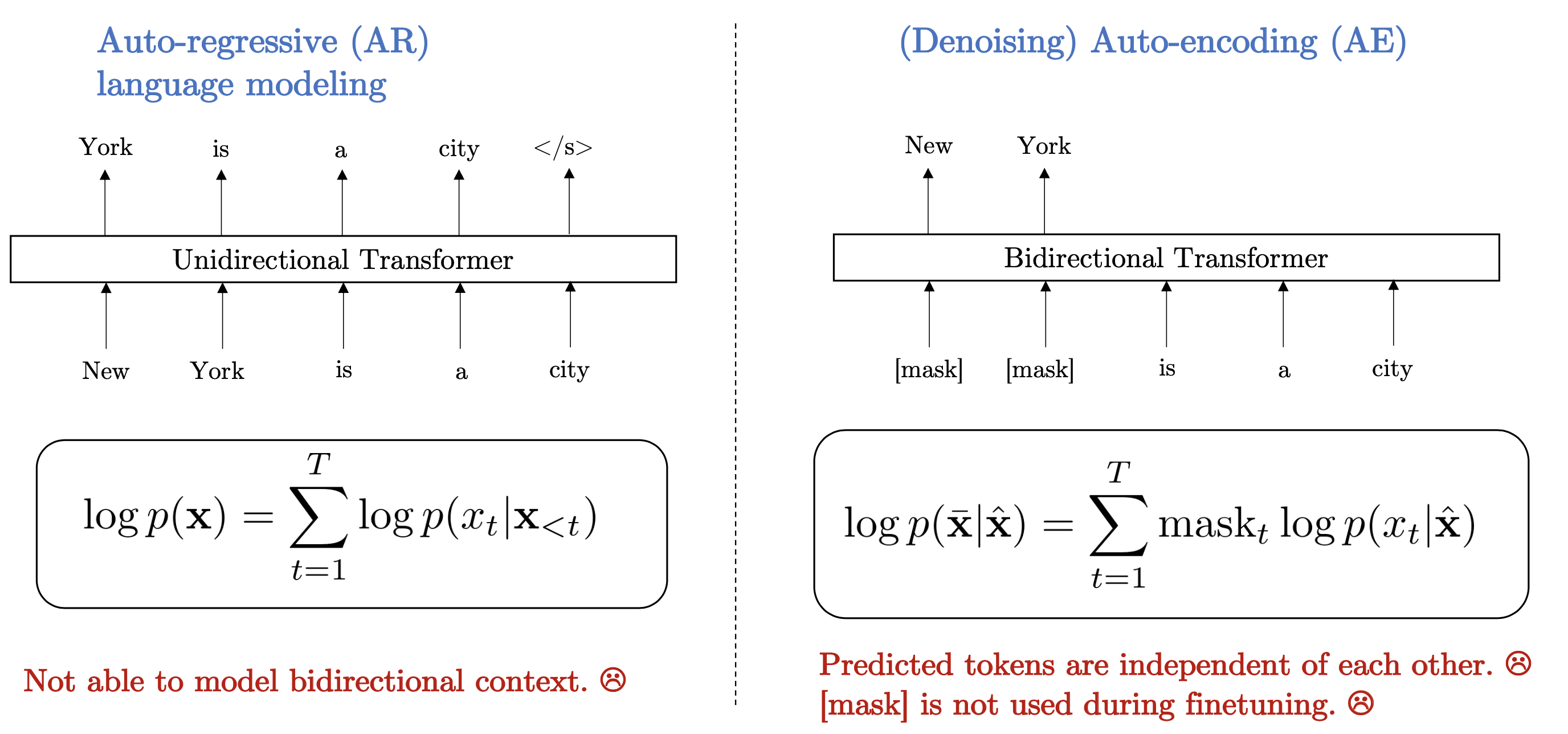

FIGURE 9.1: Autoencoding

Autoencoding(AE) have been most successful pre-training objectives and figure 9.1 shows the modeling of it. AE based model does not perform explicit density estimation but instead aims to reconstruct the original data from corrupted input. Specifically, given a text sequence \(X = (x_1,...,x_T)\), AE factorizes the log-likelihood into a partial sum \[log p(\bar{X}|\hat{X}) = \sum^T_{t=1} mask_t p(x_t|\hat{X})\], where \(mask_t\) is an indicator to show if a token is masked,Yang et al. (2019).

The training objective is to reconstruct the masked tokens \(\bar{X}\) given the sequence \(\hat{X}\). AE tries to find the best model \(P\) to predict the masked tokens. The BERT introduced next is one of the most important AE models.

9.1.2 Introduction of BERT

BERT is published by researchers at Google AI in 2018. It is regarded as a milestone in the NLP community by proposing a bidirectional Language model based on Transformer.

BERT is a notable example of AE and it uses the structure of the AE model just mentioned, which means that some tokens in the training data will be masked. In BERT 15% of tokens are replaced by a special symbol [MASK], and the model is trained to reconstruct the original sequence from the masked tokens. By contrast with previous efforts that looked at a text sequence either from left to right(RNN chapter 5) or combined left-to-right and right-to-left training (ELMO chapter 8), the Transformer Encoder (chapter 9) utilizes bidirectional contexts simultaneously. Therefore BERT uses the Transformer Encoder as the structure of the pre-train model and addresses the unidirectional constraints by proposing new pre-training objectives: the Masked Language Model(MLM) and Next-sentence Prediction(NSP).

The special pre-training structure of BERT enables it to pre-train deep bidirectional representations and after fine-tuning based the representations, BERT advances state-of-the-art performance for eleven NLP tasks. Its unique structural ideas and excellent model performance make BERT the most important NLP model at present.

9.1.3 Input Representation of BERT

For NLP models, the input representation of the sequence is the basis of excellent model performance, many scholars have conducted in-depth research on methods to obtain word embeddings for a long time chapter 4. As for BERT, due to the model structure, the input representations need to be able to unambiguously represent both a single text sentence or a pair of text sentences in one token sequence. For a given token, its input representation is constructed by summing the corresponding token, segment, and position embeddings, Devlin et al. (2018).

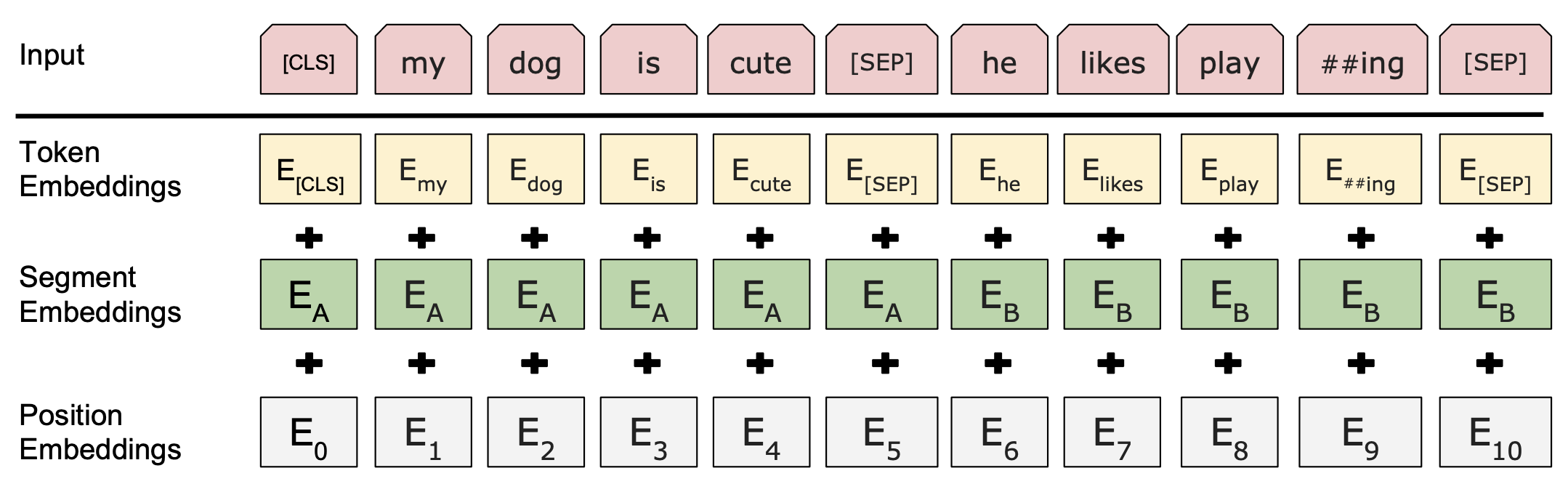

FIGURE 9.2: BERT input representation

Figure 9.2 is the visual representation of input representations of BERT tokens. The specifics are:

As for Token Embeddings (yellow block): Use WordPiece embeddings Wu et al. (2016) with a 30,000 token vocabulary and split word pieces denoted with ##. e.g.[ playing = play and ##ing ] and the first token of every sequence is always the special classification embedding [CLS]. For non-classification tasks, this vector is ignored. Sentence pairs are packed together into a single sequence and are separated with a special token [SEP].

As for Segment Embeddings (green block): For the input is a sequence with two sentences, different learned sentence embedding[e.g., A and B] will be added to every token of each sentence. For single-sentence inputs, we only use the sentence A embeddings.

As for Position Embeddings (grey block): For languages, the order of each word in a sentence is quite important, so the position of each token will be marked as Position embeddings.

BERT limits the length of the entire sequence to no more than 512 tokens. Whether it is a one-sentence sequence or a sentence-pairs sequence, sequences exceeding 512 will be divided at intervals of 512 tokens. In practice, considering computational efficiency, BERT mostly divides the sequence with a length of 128 tokens.

Finally, BERT adds these three types of embeddings to get the final input representation. And BERT will use the input representation obtained above to pre-train the model, below we respectively introduce how BERT uses MLM and NSP for pre-training.

9.1.4 Masked Language Model

![BERT Masked Language Model

Alammar, Jay (2018). The Illustrated BERT, ELMo, and co. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-bert/](figures/02-03-transfer-learning-for-nlp/bert_masked_task.png)

FIGURE 9.3: BERT Masked Language Model

Alammar, Jay (2018). The Illustrated BERT, ELMo, and co. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-bert/

Masked Language Model is the most important model structure of BERT and it mainly combines the ideas of Transformer Encoder and masked tokens.

Figure 9.3 is the visual representation of the Masked Language Model. As shown in the figure, when word embeddings are fed into BERT, 15% of the tokens in each sequence will be replaced by a special token [MASK]. Here, token [improvisation] is replaced with [MASK]. The output of MLM is the word embeddings of corresponding tokens, then feed the word embedding of [MASK] token into a simple softmax classifier and get the final prediction of [MASK] token. The task of MLM is to predict the original value of masked tokens, we hope that the result obtained by the softmax classifier is close to the true value. And the most important part is the “yellow” block, it’s basically a multi-layer bidirectional Transformer Encoder based on implementation described in Kaiser et al. (2017).

Here I summarize the main points of MLM in the form of question and answer as follows:

- What is the Masked Language Model?

- 15% of all WordPiece tokens in each sequence will be randomly masked.

- Input: token embedding(one sequence, begin with [CLS])

- Output: BERT token embedding.

- Using softmax classifier to predict the masked token. (words match each other may have the same BERT embedding)

- How to mask?

- 80% of the time: Replace the word with the [MASK] token, e.g., my dog is hairy \(\Rightarrow\) my dog is [MASK]

- 10% of the time: Replace the word with a random word,e.g., my dog is hairy \(\Rightarrow\) my dog is apple.

- 10% of the time: Keep the word unchanged, e.g., my dog is hairy \(\Rightarrow\) my dog is hairy.

- Why there are two other methods to replace the word?

- Why keep 10% of masked tokens unchanged?

In some downstream tasks like POSTagging, all the tokens are known, if BERT only trained the Masked sequences, then the model only uses the information of context, exclude the information of the masked words. It will lose a part of the information, then weakens the performance of the model. - Why replace 10% of the masked tokens with random words?

Since we keep 10% of the masked token unchanged, if we do not add random noise, the model will be “lazy” in our training, the model will plagiarize current tokens, rather than learning.

- Why keep 10% of masked tokens unchanged?

9.1.5 Next-sentence Prediction

![BERT Next-sentence Tasks

Alammar, Jay (2018). The Illustrated BERT, ELMo, and co. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-bert/](figures/02-03-transfer-learning-for-nlp/bert_nsp.png)

FIGURE 9.4: BERT Next-sentence Tasks

Alammar, Jay (2018). The Illustrated BERT, ELMo, and co. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-bert/

Figure 9.4 is the visual representation of Next-sentence Prediction(NSP). Many important downstream tasks such as Question Answering (QA) and Natural Language Inference (NLI) are based on understanding the relationship between two text sentences, which is not directly captured by language modeling. So BERT proposes the NSP by using the special token [CLS] as the first token of every sequence. The pre-training structure of NSP and MLM are the same, and NSP and MLM are trained together. NSP using token [CLS] to get the result. For example, token [CLS] will get a binary classification prediction through the softmax classifier, which represents whether the model believes that the sentiment of the two sentences in the input sequence is the same.

Here I also use the question and answer format to summarize the main points of NSP:

- What is Next-sentence Prediction?

- Input: token embedding (two sentences, begin with [CLS], each sentence ends with [SEP])

- Output: BERT token embedding.

- Using a softmax classifier to explain the relationship between two sentences.

- Using [CLS] token to pre-train classification tasks.

- Sentences can be trivially generated from a monolingual corpus.

- Choose sentences A and B for each example, 50% of B is the actual next sentence that follows A, and 50% of B is a random sentence from the corpus.

- For example:

- Input = [CLS] the man went to [MASK] store [SEP] he bought a gallon [MASK] milk[SEP]

Label = IsNext. - Input = [CLS] the man [MASK] to the store [SEP] penguin [MASK] are flight ##less birds [SEP].

Label = NotNext.

- Input = [CLS] the man went to [MASK] store [SEP] he bought a gallon [MASK] milk[SEP]

9.1.6 Pre-training Procedure of BERT

For the pre-training corpus, BERT uses the concatenation of BooksCorpus (800M words) (Zhu et al., 2015) and English Wikipedia (2,500M words) to create two versions of BERT (L stands for the number of layers, H stands for the hidden size, A stands for the number of self-attention heads):

- BERT-Base: L = 12, H = 768, A = 12, Total parameters = 110M

- BERT-Large: L = 24, H = 1024, A = 16, Total parameters = 340M

9.1.7 Fine-tuning Procedure of BERT

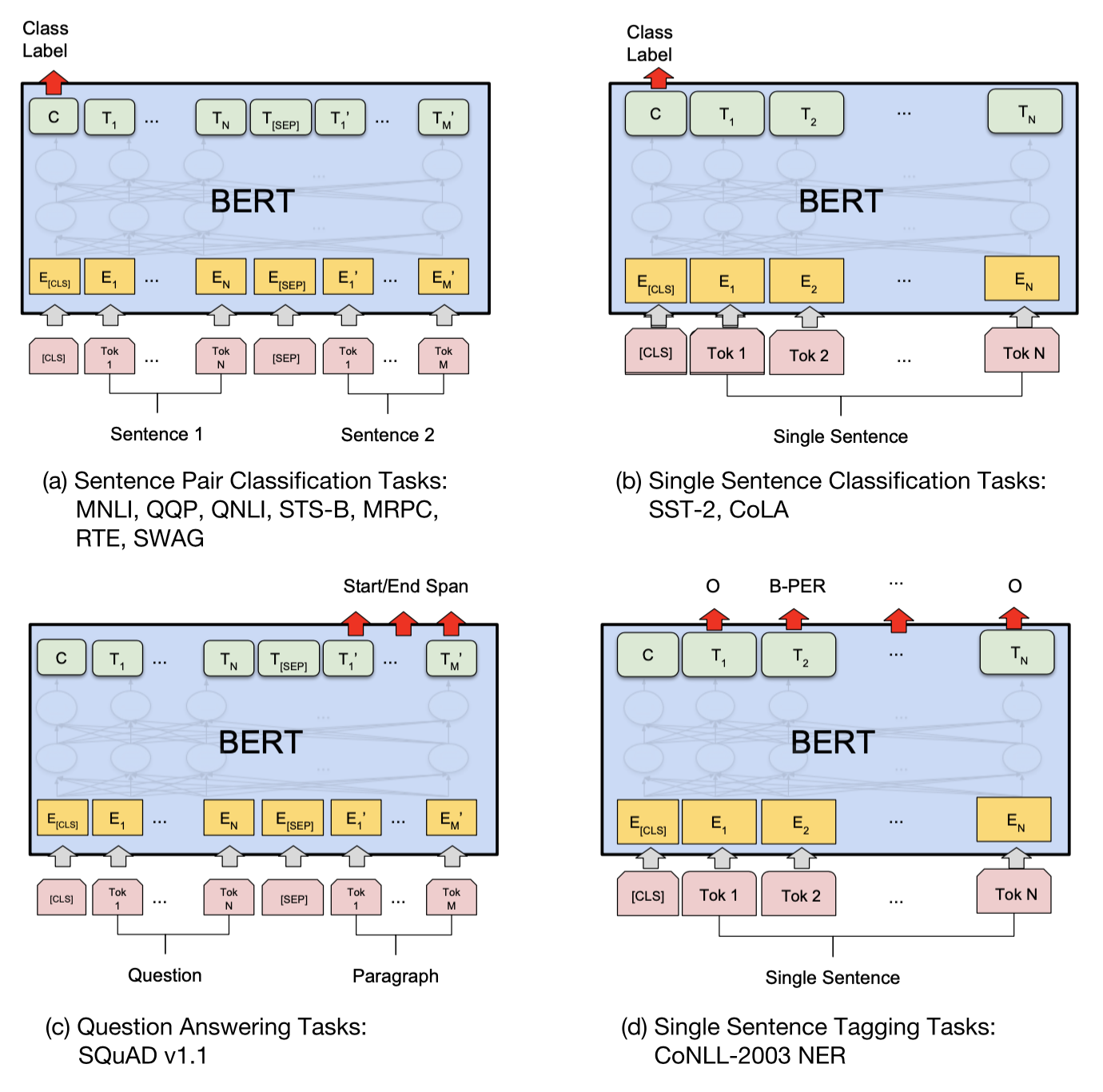

FIGURE 9.5: BERT Task Specific Models

For the BERT model obtained by pre-training, different types of tasks require different modifications to the model, and the modification of the model before fine-tuning is quite simple. As shown in Figure 9.5:

As for the sequence-level classification problem, such as sentiment analysis, task (a) and (b) in the figure, BERT takes the output representation of the first token[CLS] then feeds it to a softmax classifier to get the classification prediction and uses this prediction as model output for fine-tuning.

As for the Question Answering Task (e.g.Reading comprehension, task(c)), BERT needs to find the correct answer in the latter sentence to answer the question raised by the previous sentence. For each token in the second sentence, BERT will use the output embeddings of the token to make two predictions, representing whether the token is the beginning or the end of the answer. For example, if the third token of the second sentence is considered to be the beginning of the answer, and the fifth token is considered to be the end of the answer, then BERT will use the third token to the fifth token as the result to answer the questions raised by the first sentence. If the fifth token is considered to be the beginning of the answer and the third token is considered to be the end of the answer, that is, the end appears before the beginning, then the resulting output by BERT will be: No Answer. The true answer in reading comprehension may happen to be No Answer. BERT performs fine-tuning by comparing the loss between the prediction and the true value. It is worth noting that in reading comprehension or summarization tasks, BERT is not doing real summarization. It cannot generate new vocabulary by itself, but can only choose from the vocabulary of the latter sentence. This may be the reason why BERT does not perform so well in corresponding tasks.

As for token-level classification (e.g. NER, Task (d) in the figure), BERT takes the output of the last layer transformer of all tokens then feeds it to the softmax layer for classification and uses the prediction of each token of the model to compare with the real answer and fine-tune the parameters.

9.1.8 Feature Extraction

Like many other Language models, the pre-trained BERT can create contextualized word embeddings. Then the word embeddings can be used as features in other models. Readers can try out BERT through BERT FineTuning with Cloud TPUs.

9.1.9 BERT-like models

The state-of-the-art performance of BERT reveals the deep bidirectional language model can significantly improve the model performance in NLP tasks, and BERT chart a new course that how a real bidirectional model should be.

However, BERT has also the following weaknesses:

- First of all, the input to BERT contains artificial symbols like [MASK] that never occur in downstream tasks, which creates a pre-train-fine-tuning discrepancy problem.

- Secondly, BERT assumes the predicted tokens are independent of others given the unmasked tokens, which is oversimplified for natural language.

Several models are inspired by BERT to solve these problems:

Roberta Liu et al. (2019) shows hyperparameter choices have a significant impact on the final results. It improves BERT pre-training in the following aspects to get better performance:

- Changing the input embedding to Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) Sennrich, Haddow, and Birch (2015).

- Using dynamic masking: each train has different training data.

- Using full sentence without NSP.

- More Data, larger batch size (8k), and longer training (100k to 300k steps).

ALBERT Lan et al. (2019) mainly makes three improvements to BERT, which reduces the overall parameter amount, accelerates the training speed, and improves the model performance under the same training time.

- Using factorized embedding parameterization.

- Cross-layer parameter sharing, which significantly reduces the number of parameters.

- Replacing NSP with Sentence-order prediction loss (SOP).

There are also BERT-like models pre-trained on domain-specific corpora, for example, SciBERT Beltagy, Lo, and Cohan (2019) on scientific publications, ERNIE Zhang et al. (2019) on a large corpus incorporating knowledge graph in the input. In comparison to fine-tune original BERT, training on the domain-specific corpora then fine-tuning them on downstream NLP tasks has shown to yield better performance.

9.2 Generative Pre-Training(GPT-2)

The GDP-2 mentioned next is also the most important NLP model in recent years. It and BERT are often mentioned at the same time because the model structure it uses is also based on the transformer, but it is the transformer decoder. As mentioned in chapter 9, the transformer decoder can be regarded as a unidirectional language model, so GDP-2 represents a different way of thinking from BERT and has the surprising ability in writing tasks.

9.2.1 Auto-regressive Language Model(AR)

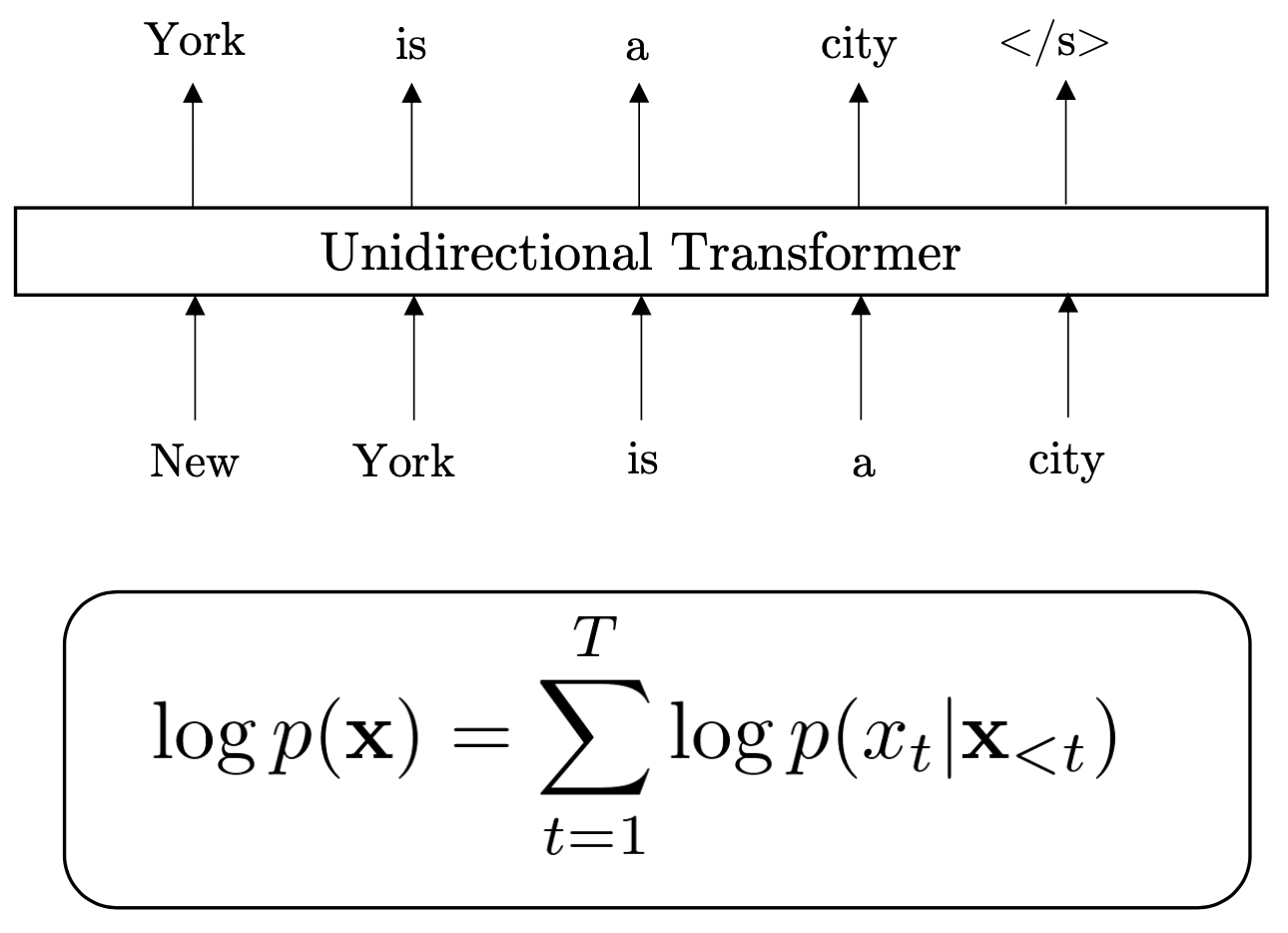

FIGURE 9.6: Autoregressive

GPT-2 is a unidirectional language model, such model structure is also called Auto-regressive language model. Figure 9.6 shows the modelling of Auto-regressive language model, it tries to estimate the probability distribution of a sequence with a auto-regressive pattern. Specifically, given a text sequence \(X = (x_1,...,x_T)\), AR language model factorizes the log-likelihood into a forward sum \(logp(x) = \sum^T_{t=1} p(x_t|x<t)\) or a backward one \(logp(x) = \sum^{t=1}_{T} p(x_t|x>t)\) Yang et al. (2019). Since an AR language model is only trained to encode a uni-directional context (either forward or backward), it is not effective at modeling deep bidirectional contexts. On the contrary, downstream language understanding tasks often require bidirectional context information.

9.2.2 Introduction of GPT-2

GPT-2 is proposed by researchers at OpenAI in 2019. It captures the attention of the NLP community for the following characters:

Instead of the fine-tuning model with specific tasks, GPT-2 demonstrates language models can perform down-stream tasks in a zero-shot setting, which means without any parameter or architecture modification.

To perform better under the zero-shot setting, GPT-2 becomes extremely large. The result is that training GPT-2 needs enormous data, so researchers also create a new dataset WebText, which contains millions of webpages.

With the characters above, GPT-2 achieves state-of-the-art results on 7 out of 8 tested language modeling datasets in a zero-shot setting but still underfits WebText.

Readers can experiment with GPT-2 by using AllenAI GPT-2. You can input a sentence and see the prediction of the next words.

9.2.3 Input Representation of GPT-2

GPT-2 uses a human-curated dataset called WebText, that contains text scraped from 45 million web-links. All results presented in paper use a preliminary version of WebText, which contains slightly over 8 million documents for a total of 40GB of text after de-duplication and some heuristic-based cleaning Radford et al. (2019).

![GPT-2 Input Representation

Alammar, Jay (2018). The Illustrated GPT-2 co. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-gpt2/](figures/02-03-transfer-learning-for-nlp/gpt_input_representation.png)

FIGURE 9.7: GPT-2 Input Representation

Alammar, Jay (2018). The Illustrated GPT-2 co. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-gpt2/

Figure 9.7 shows the input representation of GPT-2. The input sequence has a start token [S], and input embedding of each token is the corresponding specially designed Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) Sennrich, Haddow, and Birch (2015), adding up the positional encoding vector.

9.2.4 The Decoder-Only Block

![GPT-2 Model

Alammar, Jay (2018). The Illustrated GPT-2 co. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-gpt2/](figures/02-03-transfer-learning-for-nlp/gpt_decoder.png)

FIGURE 9.8: GPT-2 Model

Alammar, Jay (2018). The Illustrated GPT-2 co. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-gpt2/

Figure 9.8 shows the model of GPT-2. This model essentially is the Transformer decoder, except they threw away the second self-attention layer. In each decoder, Layer normalization Ba, Kiros, and Hinton (2016) is moved to the input of each sub-block, similar to a pre-activation residual network He et al. (2016b), and an additional layer normalization is added after the final self-attention block. A modified initialization which accounts for the accumulation on the residual path with model depth is used Radford et al. (2019).

GPT-2 reads from the start token [s] till the last predicted token to predict the next token. For example, in the first round, model uses [s] to predict [robot], in the next round the input is updated as {[s],[robot]} since [robot] has been predicted. This is how Masked self-Attention in Decoder block works.

Otherwise, since a general system should be able to perform many different tasks, even for the same input, it should condition not only on the input but also on the task to be performed. The model of GPT-2 should be : \[log p(x)=log\sum^{n}_{i=1}p(s_n|s_1,...,s_{n-1};task_i)\]

For example, a translation training example can be represented as the sequence (Translate to the french, English text, French text). Likewise, a reading comprehension training example can be written as (Answer the question, Document, Question, Answer).

By using the specially designed WebText, GPT-2 can be used by following patterns for different tasks.

Reading Comprehension: data sequence, “Q:”, question sequence, “A:”

Summarization: data sequence, “TL;DR:”

Translation: English sentence 1 = French sentence 1, English sentence 2 = French sentence 2, “English sentence 3 =”

9.2.5 GPT-2 Models

| Parameters | Layers | Dimensionality |

|---|---|---|

| 117M | 12 | 768 |

| 345M | 24 | 1024 |

| 762M | 36 | 1280 |

| 1542M | 48 | 1600 |

Four versions models are trained, the architectures are summarized in 9.1. The smallest model is equivalent to the original GPT, and the second smallest equivalent to the largest model from BERT Devlin et al. (2018). The largest model is called GPT-2, which has 1.5 billion parameters.

9.2.6 Conclusion

The framework of GPT-2 is the combination of pre-training based on Transformer Decoder and fine-tuning based on unsupervised downstream tasks.

After the great success of bidirectional models like BERT, GPT-2 insists on using unidirectional models and still achieves state-of-the-art performance. It proves that the performance of language models can be significantly improved by simply increasing the size of training datasets and models, which is exactly what GPT-2 did and even GPT-2, which has 1.5 billion parameters, still underfits WebText. This result also suggests that datasets are as important as models.

9.3 XLNet

9.3.1 Introduction of XLNet

FIGURE 9.9: AR Language Modeling and AE

XLNet is proposed by researchers at Google in 2019. Since the autoregressive language model (e.g.GPT-2) is only trained to encode a unidirectional context and not effective at modeling deep bidirectional contexts and autoencoding (e.g.BERT) suffers from the pre-train-fine-tune discrepancy, XLNet borrows ideas from the two types of objectives while avoiding their limitations.

It is a new objective called Permutation Language Modeling. By using a permutation operation during training time, bidirectional context information can be captured and makes it a generalized order-aware autoregressive language model. Besides, XLNet introduces a two-stream self-attention to solve the problem that standard parameterization will reduce the model to bag-of-words.

Two XLNet are released, i.e. XLNet-Base and XLNet-Large, and include the similar settings of corresponding BERT. Empirically, XLNet outperforms BERT on 20 tasks and achieves state-of-the-art results on 18 tasks.

9.3.2 Permutation Language Modeling(PLM)

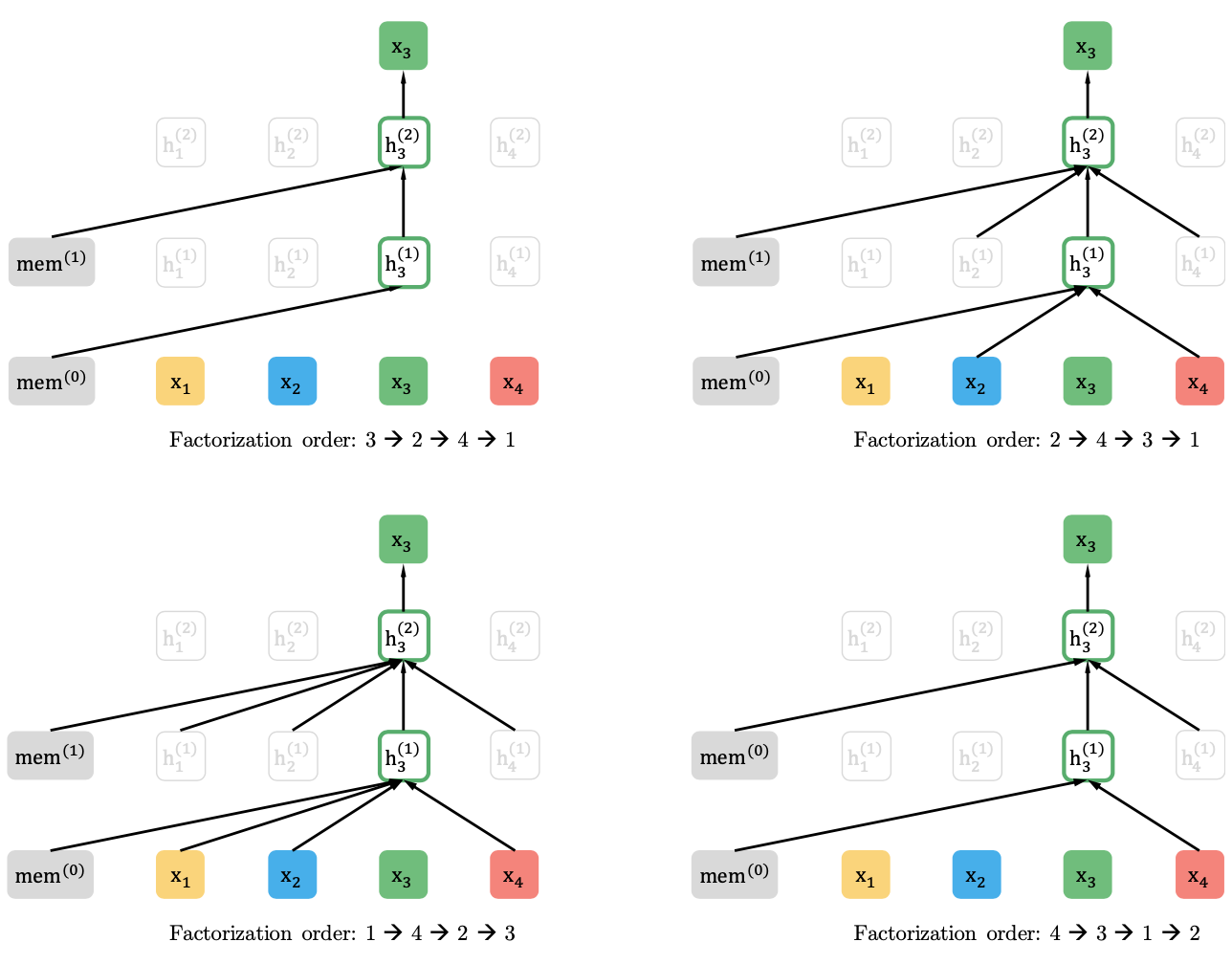

Now Figure 9.10 illustrates the permutation language modeling objective.

FIGURE 9.10: Illustration of the permutation language modeling objective for predicting x3 given the same input sequence x but with different factorization orders.

Specifically, for a sequence \(X\) of length \(T\), there are \(T!\) different orders to perform a valid autoregressive factorization. Intuitively, if model parameters are shared across all factorization orders, in expectation, the model will learn to gather information from all positions on both sides. Let \(P_T\) be the set of all possible permutations of a sequence [1,2,…, T] and use \(z_t\) and \(z_{<t}\) to denote the t-th element and the first t−1 elements of a permutation \(p\in P_T\). Then the permutation language modeling objective can be expressed as follows:

For instance, assume we have a input sequence {I love my dog}.

In the upper left plot of the above Figure 9.10, when we have a factorization order: {3, 2, 4, 1}, the probability of sequence can be expressed as follows:

as for the third token: {my}, it cannot use the information of all other tokens, so only one arrow from the starting token points to the third token in the plot.

In the upper right plot of the above Figure 9.10, when we have a factorization order: {2, 4, 3, 1}, the probability of sequence can be expressed as follows:

as for the third token: {my}, it can use the information of the second and fourth tokens because it places after these two tokens in the factorization order. Correspondingly, it cannot use the information of the first token. So in the plot, in addition to the arrow from the starting token, there are arrows from the second and fourth tokens pointing to the third token. The rest two plots in the figure have the same interpretation.

During training, for a fixed factorization order, XL-Net is a unidirectional language model based on the transformer decoder, which performs normal model training. But different factorization order makes the model see different order of words when traversing sentences. In this way, although the model is unidirectional, it can also learn the bidirectional information of the sentence.

It is noteworthy that the sequence order is not actually shuffled but only attention masks are changed to reflect factorization order. With PLM, XLNet can model bidirectional context and the dependency within each token of the sequence.

9.3.3 The problem of Standard Parameterization

As just mentioned, XL-Net is a language model when the factorization order is fixed, which means that we want the model to be able to predict the t-th word under the condition of knowing the word before t.

The Standard Parameterization can be expressed as follows:

\[p_{\theta}(X_{p_t}=x|x_{p<t})=\frac{e(x)^Th_{\theta}(x_{p<t})}{\sum_{x^{'}}e(x^{'})^Th_{\theta}(x_{p<t})}\] where \(e(x)\) denotes the embedding of input token and \(h_{\theta}(x_{p<t})\) denotes the hidden representation of \(x_{p<t}\).

While the permutation language modeling objective has desired properties, naive implementation with standard Transformer parameterization may not work. Specifically, let’s consider two different permutations \(p^1\text{:{I love my dog}}\) and \(p^2:\text{{I love dog my}}\). The probability of \(\text{{my}}\) in \(p^1\): \(\text{P(my|I, love)}\) and the probability of \(\text{{dog}}\) in \(p^2\): \(\text{P(dog|I, love)}\)are identical. The model will be reduced to predicting a bag-of-words, because \(h_{\theta}(x_{z<t})\) does not contain the position of the target.

XLNet resolves the problem by reparameterizing with positions:

\[p_{\theta}(X_{p_t}=x|x_{p<t})=\frac{e(x)^Tg_{\theta}(x_{p<t},p_t)}{\sum_{x^{'}}e(x^{'})^Tg_{\theta}(x_{p<t},p_t)}\]

where \(e(x)\) denotes the embedding of input token and \(g_{\theta}(x_{p<t},p_t)\) denotes the hidden representation of \(x_{p<t}\) and position \(p_t\).

But reparameterization with positions brings another contradiction Yang et al. (2019):

(1) To predict the token \(x_{p_t}\) , \(g_{\theta}(x_{p<t},p_t)\) should only use the position \(p_t\) and not the content \(x_{p_t}\), otherwise the objective becomes trivial.

(2) To predict the other tokens \(x_{p_j}\) with j > t, \(g_{\theta}(x_{p<t},p_t)\) should also encode the content \(x_{p_t}\) to provide full contextual information.

XLNet proposes the Two-Stream Self-Attention to resolve the contradiction.

9.3.4 Two-Stream Self-Attention

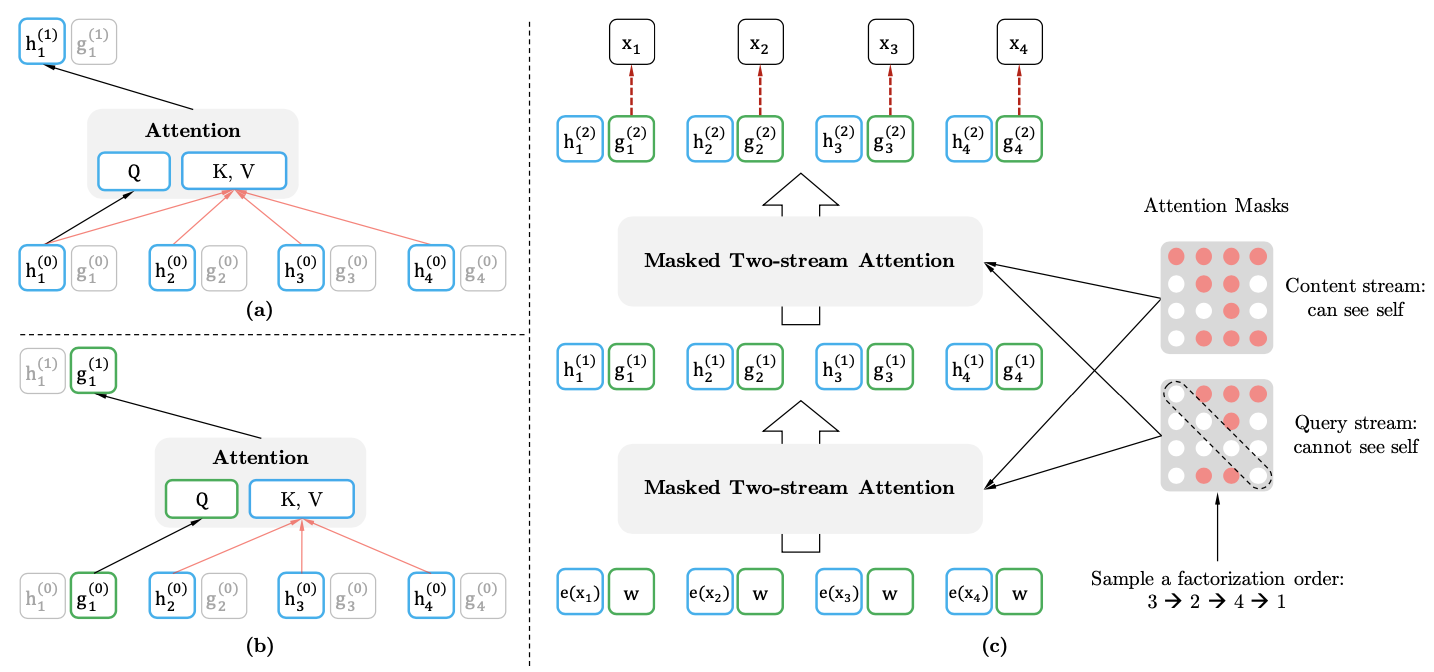

FIGURE 9.11: Two-Stream Self-Attention

Instead of one, two sets of hidden representation are proposed:

- The content representation \(h_{\theta}(x_{p \leq t})\), this representation encodes both the context and \(x_{p_t}\) itself.

- The query representation \(g_{\theta}(x_{p<t},p_t)\), which only has information \(x_{p<t}\) and the position \(p_t\) but not the content \(x_{p_t}\).

Figure 9.11 is an example with the Factorization order: \(3,2,4,1\):

\(h_i^{(t)}\) denotes the content representation of the i-th token in the t-th layer of self-attention. It is the same as the standard self-attention. For instance, \(h_1^{(1)}\) can see all the \(h_i^{(0)}\) since the 1-st token is after token \({3,2,4}\).

\(g_i^{(t)}\) denote the query representation of the i-th token on the t-th layer of self-attention. It does not have access information about the content \(x_{p_t}\), other trivial.

Computationally, \(h_i^{(0)}\) is the word embeddings, and \(g_i^{(0)}\) is a trainable parameter initialized with a trainable vector. Only \(h_i^{(t)}\) is used during fine-tuning. The last \(g_i^{(t)}\) is used for optimizing the LM loss. A self-attention layer \(m=1,..., M\) are schematically updated with a shared set of parameters as follows:

\[ h_{p_t}^{m} \leftarrow Attention (Q=h_{p_t}^{m-1}, KV=h^{(m-1)}_{p \leq t};\theta) \text{ (content stream: use both $p_t$ and $x_{p_t}$)} \\ g_{p_t}^{m}\leftarrow Attention (Q=g_{p_t}^{(m-1)}, KV=h^{(m-1)}_{p<t};\theta) \text{ (query stream: use $p_t$ but cannot see }x_{p_t}) \]

where Q, K, V denote the query, key, and value in an attention operation Vaswani et al. (2017). More details are included in Appendix A.2 for reference Yang et al. (2019).

9.3.5 Partial Prediction

While the PLM has several benefits, optimization is challenging due to the permutation operator. To reduce the optimization difficulty, XLNet only predicts the last tokens in a factorization order. It sets a cutting point \(c\) and split the permutation \(p\) into a non-target subsequence \(p_{\leq c}\) and a target subsequence \(p_{>c}\). The objective is to maximize the log-likelihood of the target subsequence conditioned on the non-target subsequence, i.e.,

\[\begin{equation} \max_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_{p\sim P_T} \left[logp_{\theta}(x_{z_{>c}|x_{z_{\leq c}}})\right] = \mathbb{E}_{p\sim P_T} \left[\sum_{t=c+1}^{|z|} logp_{\theta}(x_{z_t|x_{z_{\leq t}}})\right] \end{equation}\] For unselected tokens, their query representations need not be computed, which saves speed and memory. XLNet incorporates ideas from Transformer-XL and inherits two important characters of it, i.e. Segment-Level Recurrence and Relative Position Encoding, to enable the learning of long-term dependency and resolve the context fragmentation Dai et al. (2019). There is also a good Blog to introduce Transformer-XL, Readers can read if interested.

9.3.6 XLNet Pre-training Model

After tokenization with SentencePiece Kudo and Richardson (2018), Researchers obtain 2.78B, 1.09B, 4.75B, 4.30B, and 19.97B subword pieces for Wikipedia, BooksCorpus, Giga5, ClueWeb, and Common Crawl respectively, which are 32.89B in total, to pre-train the XLNet.

Analogous to BERT, two versions of XLNet have been trained:

- XLNet-Base: L = 12, H = 768, A = 12, Total parameters = 110M (on BooksCorpus and Wikipedia only)

- XLNet-Large: L = 24, H = 1024, A = 16, Total parameters = 340M (on total datasets)

9.3.7 Conclusion

Language modeling has been a rapidly developing research area. However, most language modelings are unidirectional and BERT Devlin et al. (2018) shows that bidirectional modeling can significantly improve model performance. Unidirectional modelings without specific structure are hard to capture the bidirectional context. Now with the permutation operator, the unidirectional language modelings can become bidirectional modeling. XLNet has built a bridge between language modeling and bidirectional models. Overall, XLNet is a generalized AR pre-training method that uses a permutation language modeling objective to combine the advantages of AR and AE methods.

9.4 Latest NLP models

Nowadays NLP has become a competition between big companies. When BERT first came, people talked about it may cost thousands of dollars to train it. Then came GPT-2, which has 1.5 billion parameters and is trained on 40GB data. As I mentioned above, GPT-2 of Open-AI shows that increasing the size of models and datasets is at least as important as proposing a new model architecture.

After GPT-2, researchers at Google did the same thing, they proposed a general language model called T5 Raffel et al. (2019), which is trained on 750GB corpus - “C4 (Colossal Clean Crawled Corpus)”. If you read the paper, you will find that the last page of it is a table of several experience results, which may cost millions of dollars to reproduce it.

On 28th May 2020, the “Arms race” goes into another level, GPT-3 Brown et al. (2020) emerged, the new paper takes GPT to the next level by making it even bigger - GPT-3 has 175 billion parameters and is trained on a dataset that has 450 billion of tokens “GPT-3 Dataset”. GPT-3 experiments with the three different settings: zero-shot, one-shot, and Few-shot to show that scaling up language models can greatly improve performance, sometimes even reaching competitiveness with prior SOTA approaches. However, it is conservatively estimated that training GPT-3 will cost one hundred million dollars.

Models like T5 and GPT-3 are very impressive, but the biggest problem at the moment is to find a way to make the current model put into use in the industry. If it can’t bring benefits, the AI industry can’t be sustained by burning money. As for researchers, the truth is, with the resources it is also possible to fail, but it is certainly impossible to succeed without resources now.

References

Ba, Jimmy Lei, Jamie Ryan Kiros, and Geoffrey E Hinton. 2016. “Layer Normalization.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1607.06450.

Beltagy, Iz, Kyle Lo, and Arman Cohan. 2019. “SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text.” In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Emnlp-Ijcnlp), 3606–11.

Brown, Tom B., Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, et al. 2020. “Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners.”

Dai, Zihang, Zhilin Yang, Yiming Yang, Jaime Carbonell, Quoc V Le, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. 2019. “Transformer-Xl: Attentive Language Models Beyond a Fixed-Length Context.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1901.02860. https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.02860.

Devlin, Jacob, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2018. “BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding.” CoRR abs/1810.04805. http://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805.

He, Kaiming, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun. 2016b. “Identity Mappings in Deep Residual Networks.” In European Conference on Computer Vision, 630–45. Springer.

Kaiser, Lukasz, Aidan N Gomez, Noam Shazeer, Ashish Vaswani, Niki Parmar, Llion Jones, and Jakob Uszkoreit. 2017. “One Model to Learn Them All.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1706.05137.

Kudo, Taku, and John Richardson. 2018. “Sentencepiece: A Simple and Language Independent Subword Tokenizer and Detokenizer for Neural Text Processing.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1808.06226.

Lan, Zhenzhong, Mingda Chen, Sebastian Goodman, Kevin Gimpel, Piyush Sharma, and Radu Soricut. 2019. “Albert: A Lite Bert for Self-Supervised Learning of Language Representations.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1909.11942.

Liu, Yinhan, Myle Ott, Naman Goyal, Jingfei Du, Mandar Joshi, Danqi Chen, Omer Levy, Mike Lewis, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Veselin Stoyanov. 2019. “Roberta: A Robustly Optimized Bert Pretraining Approach.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1907.11692. https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.11692.

Radford, Alec, Jeffrey Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, and Ilya Sutskever. 2019. “Language Models Are Unsupervised Multitask Learners.”

Raffel, Colin, Noam Shazeer, Adam Roberts, Katherine Lee, Sharan Narang, Michael Matena, Yanqi Zhou, Wei Li, and Peter J Liu. 2019. “Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1910.10683. https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.11942.

Sennrich, Rico, Barry Haddow, and Alexandra Birch. 2015. “Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1508.07909.

Vaswani, Ashish, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. “Attention Is All You Need.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 5998–6008.

Wu, Yonghui, Mike Schuster, Zhifeng Chen, Quoc V Le, Mohammad Norouzi, Wolfgang Macherey, Maxim Krikun, et al. 2016. “Google’s Neural Machine Translation System: Bridging the Gap Between Human and Machine Translation.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1609.08144.

Yang, Zhilin, Zihang Dai, Yiming Yang, Jaime Carbonell, Russ R Salakhutdinov, and Quoc V Le. 2019. “XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32, edited by H. Wallach, H. Larochelle, A. Beygelzimer, F. dAlché-Buc, E. Fox, and R. Garnett, 5753–63. Curran Associates, Inc. http://papers.nips.cc/paper/8812-xlnet-generalized-autoregressive-pretraining-for-language-understanding.pdf.

Zhang, Zhengyan, Xu Han, Zhiyuan Liu, Xin Jiang, Maosong Sun, and Qun Liu. 2019. “ERNIE: Enhanced Language Representation with Informative Entities.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1905.07129.